prominent abolitionist lecturer and novelist. He was born into slavery in the South but managed to escape to the North in 1834. His mother had William by George Higgins, a white planter who was a cousin to the owner. The owner, Dr. Young, had promised Higgins that he would not sell his son (as Higgins recognized William as such) but William ended up being sold many times before he was 20 years old. In Buffalo, New York, he aided slaves escape by means of the Underground Railroad and he became active in the abolitionist movement by joining numerous anti-slavery societies such as the Negro Convention Movement. He lectured in England from 1849 and because of the 1850 Fugitive Law he stayed there until 1854 when the Richardson family bought his freedom (as they had done the same for Frederick Douglas).

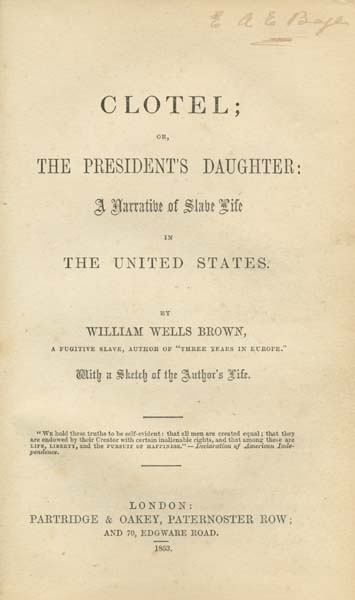

prominent abolitionist lecturer and novelist. He was born into slavery in the South but managed to escape to the North in 1834. His mother had William by George Higgins, a white planter who was a cousin to the owner. The owner, Dr. Young, had promised Higgins that he would not sell his son (as Higgins recognized William as such) but William ended up being sold many times before he was 20 years old. In Buffalo, New York, he aided slaves escape by means of the Underground Railroad and he became active in the abolitionist movement by joining numerous anti-slavery societies such as the Negro Convention Movement. He lectured in England from 1849 and because of the 1850 Fugitive Law he stayed there until 1854 when the Richardson family bought his freedom (as they had done the same for Frederick Douglas).The following excerpt is taken from the third edition of William Wells Brown's historic novel; this edition is called Clotelle, or the Colored Heroine (1867) and it is considered to be the first novel by an African-American. Brown advises his readers that the two leading characters are real personages and that the author witnessed many of the incidents.

[Quadroon; Octoroon]

A few miles out of Richmond is a pleasant place, with here and there a beautiful cottage surrounded by trees so as scarcely to be seen. Among these was one far retired from the public roads, and almost hidden among the trees. This was the spot that Henry Linwood had selected for Isabella, the eldest daughter of Agnes. The young man hired the house, furnished it, and placed his mistress there, and for many months no one in his father's family knew where he spent his leisure hours.

When Henry was not with her, Isabella employed herself in looking after her little garden and the flowers that grew in front of her cottage. The passion-flower, peony, dahlia, laburnum, and other plants, so abundant in warm climates, under the tasteful hand of Isabella, lavished their beauty upon this retired spot, and miniature paradise.

Although Isabella had been assured by Henry that she should be free and that he would always consider her as his wife, she nevertheless felt that she ought to be married and acknowledged by him. But this was an impossibility under the State laws, even had the young been disposed to do what was right in the matter. Related as he was, however, to one of the first families in Virginia, he would not have dared to marry a woman of so low an origin, even had the laws been favorable.

Here, in this secluded grove, unvisited by any other except her lover, Isabella lived for years. She had become the mother of a lovely daughter, which its father named Clotelle. The complexion of the child was still fairer than that of its mother. Indeed, she was not darker than other white children, and as she grew older she more and more resembled her father.

As time passed away, Henry became negligent of Isabella and his child, so much, so, that days and even weeks passed without their seeing him, or knowing where he was. Becoming more acquainted with the world, and moving continually in the society of young women of his own station, the young man felt that Isabella was a burden to him, and having as some would say, "outgrown his love," he longed to free himself of the responsibility; yet every time he saw the child, he felt that he owed it his fatherly care.

Henry had now entered into political life, and been elected to a seat in the legislature of his native State; and in his intercourse with his friends had become acquainted with Gertrude Miller, the daughter of a wealthy gentleman living near Richmond. Both Henry and Gertrude were very good-looking, and a mutual attachment sprang up between them.

Instead of finding fault with the unfrequent visits of Henry, Isabella always met him with a smile, and tried to make both him and herself believe that business was the cause of his negligence. When he was with her, she devoted every moment of her time to him, and never failed to speak of the growth and increasing intelligence of Clotelle.

The child had grown so large as to be able to follow its father on his departure out to the road. But the impression made on Henry’s feelings by the devoted woman and her child was momentary. His heart had grown hard, and his acts were guided by no fixed principle. Henry and Gertrude had been married nearly two years before Isabella knew anything of the event, and it was merely by accident that she became acquainted with the facts.

One beautiful afternoon, when Isabella and Clotelle were picking wild strawberries some two miles from their home, and near the roadside, they observed a one-horse chaise driving past. The mother turned her face from the carriage not wishing to be seen by strangers, little dreaming that the chaise contained Henry and his wife. The child, however, watched the chaise, and startled her mother by screaming out at the top of her voice, "Papa! papa!" and clapped her little hands for joy. The mother turned in haste to look at the strangers, and her eyes encountered those of Henry's pale and dejected countenance. Gertrude’s eyes were on the child. The swiftness with which Henry drove by could not hide from his wife the striking resemblance of the child to himself. The young wife had heard the child exclaim “Papa! Papa!” and she immediately saw by the quivering of his lips and the agitation depicted in his countenance, that all was not right.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment